Why is AWS so expensive?

Background

If you were a company that needed compute resources in the 1990’s and early 2000’s, the prevalent model was purchasing and maintaining your own servers, either in your own datacenters or through colocation services. AWS rapidly transformed the landscape with the launch of EC2 in 2006, allowing business to rent out virtualized compute on-demand, and GCP and Azure were soon to follow with the same model. Together, AWS/GCP/Azure are often referred to as the “cloud hyperscalers”, and dominate the cloud computing market.

However, there is also a different category of compute providers in the market, referred to as “bare metal” providers, who specialize in renting out entire servers on a longer term (typically monthly) basis. While none of them are as big as the hyperscalers, there is a sizable number of such providers, with Hetzner and OVHcloud being a couple of the better-known ones.

When I first started Hathora, a gaming infrastructure company, I was aware of bare metal as a concept, but had little idea of how much cheaper they actually were. Through the journey of adopting bare metal out of necessity, driven by pricing pressures from our customers and the gaming market, I’ve come to learn a lot about the fascinating cloud economics that drive the market. This article aims to shine a light on these concepts and clear up common misconceptions about what drives the price gap between on-demand cloud vendors and bare metal vendors,

For the purposes of this article I’ve picked AWS and Hetzner as representative cloud and bare metal vendors, but the same arguments hold for other vendors in their respective categories.

The Cost Gap

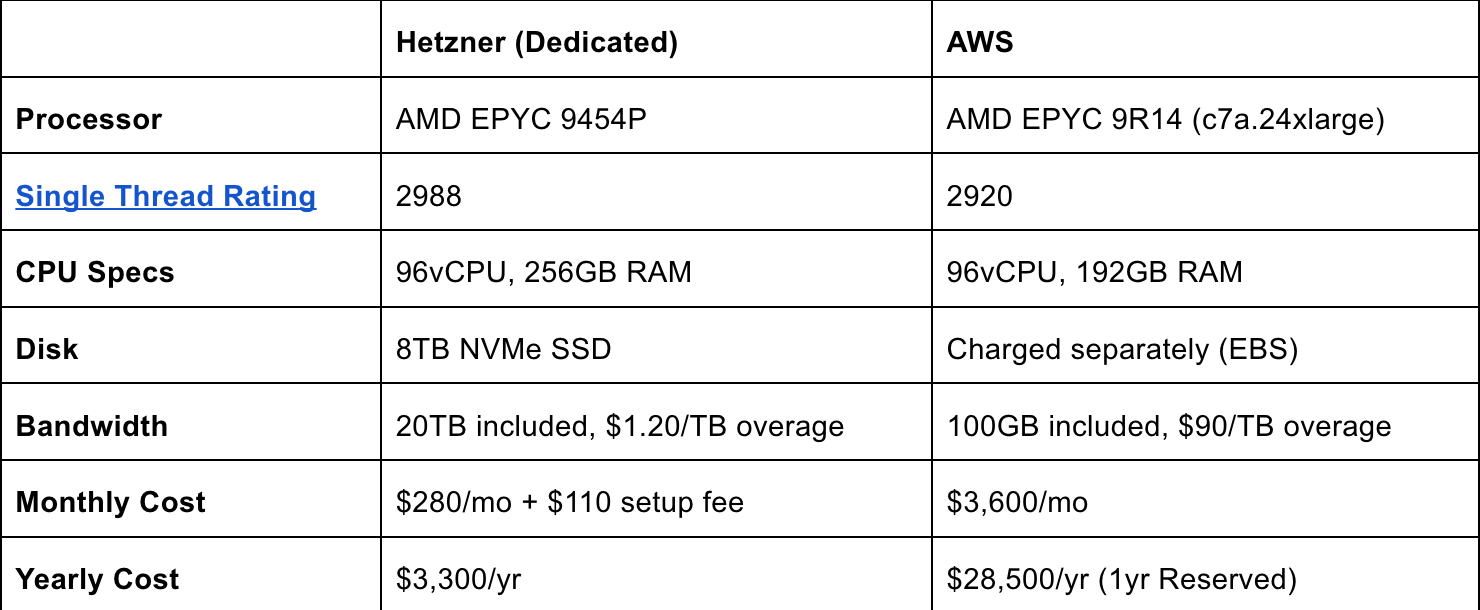

To get an idea of the cost differences between Hetzner and AWS, let’s try and compare a similar CPU instance type offered by both vendors.

Despite including more resources, Hetzner compute is 13x cheaper than AWS on a monthly basis, and 9x cheaper on a yearly basis. The difference in bandwidth costs is even more staggering – Hetzner includes 20TB of bandwidth per server per month (200x more than AWS includes), which effectively makes bandwidth free for many types of applications, and the overage bandwidth charge is 75x cheaper than AWS.

The caveat is that Hetzner Dedicated requires a minimum of 1 month reservation, whereas AWS is able to bill on-demand on a per-second basis. Despite this, it’s remarkable to see that the price to rent an equivalent Hetzner server for a whole year is cheaper than what you’d pay AWS for a single month.

Understanding the Gap

This cost difference isn’t unique to just AWS and Hetzner – it’s representative of cloud providers vs bare metal providers in general. Companies are broadly aware of this gap, and yet there are no signs of it narrowing. Let’s dive in to better understand the economic fundamentals responsible for this.

Margin

One narrative is that AWS uses its dominant market position to drive up prices beyond what competitors can charge. However, the data doesn’t support this: AWS reports a net margin of 33%, compared to Hetzner’s 28%. The slightly higher margin can’t alone account for the 13x higher compute cost.

Integrated Software Services

The next common assumption is that it’s the suite of software services that AWS offers which gives it the higher pricing power.

Hetzner’s product is fairly bare-bones – you get a dedicated server with an OS installed and a public IP address. Hetzner is responsible for ensuring the hardware remains functional (i.e. they are on the hook for detecting and rectifying any hardware failures), but they don’t help when it comes to building and operating your software.

In contrast, AWS has a number of integrated services that help solve common software challenges. These include things like security (via IAM), networking (via VPCs and ALBs/NLBs), storage (via EBS and S3), and orchestration (via ECS/EKS/Lamba). These software services themselves are either free of cost or relatively cheap – they exist primarily to drive consumption of EC2 compute and bandwidth.

For smaller teams or greenfield projects, where time-to-market matters significantly more than infrastructure spend, paying a premium to leverage these integrated services makes a lot of sense. But for larger teams or established projects, the value of these services begins to diminish, especially with the prevalence of tools like Kubernetes (for orchestration) and Wireguard (for networking) which make it easier to solve a lot of the same challenges without vendor dependencies.

Despite the significant cost premium, AWS has proven to have strong staying power even amongst larger and more established teams who have the ability with modern tooling to build vendor-angostic infrastructure. This points to deeper economic constraints holding bare metal back.

Scalability via Elasticity

The most fundamental value add that AWS brings over Hetzner is its elastic compute model. You can request compute on-demand from AWS, and be relatively confident that AWS will be able to provide you with it. Furthermore, you can shut down compute that you’re no longer using and stop getting billed for it immediately.

This elasticity is a game changer for projects with variable or unpredictable compute needs. Whereas with Hetzner you have to do accurate capacity planning and forecasting to procure the right amount of compute, with AWS it’s something you hardly ever think about. These days it’s practically unthinkable that you would have to turn new users away because you've exhausted available compute capacity – scalability in the cloud is limited by your application’s software design and implementation rather than hardware constraints.

This “promise of elasticity” is extremely expensive to maintain. AWS categorizes its hardware products via unique stock keeping unit (SKU), and it has a lot of them:

- 35 regions, each with multiple AZs (compared to 6 for Hetzner)

- 94 instance families (compared to ~15 for Hetzner)

AWS has to spend upfront capital to buy and maintain all these SKUs, not to mention the racks, networking equipment, and various associated datacenter costs. Once bought, a lot of this hardware goes underutilized due to needing to maintain sufficient buffer to fulfill peak demand. For example, consider the gaming workloads we run at Hathora: a given region can see swings as high as 10x comparing utilization during peak evening hours vs early morning. AWS needs to maintain the illusion of near-infinite elasticity, otherwise the promise of cloud (i.e. not needing to do capacity planning) is lost.

Multiply this across all 35 regions and 94 instance families, and you quickly see that AWS isn’t getting paid for a large fraction of its inventory at any given time. In contrast, Hetzner has a longer leeway to fulfill dedicated server requests, and isn’t affected nearly as much by intra-day or intra-week demand fluctuations due to its month-long reservations. Given the lack of elasticity, customers using Hetzner have to provision enough capacity for peak demand.

And thus we arrive at the root of the price gap between Hetzner and AWS – it’s representative of the cost, for both vendor and customer, of overprovisioning/underutilization. Hetzner is able to charge so little because it passes the underutilization cost to its customers, whereas AWS needs to charge what it does (and the willingness to pay exists) due to it internally absorbing the underutilization cost.

A Hybrid Approach

On a unit cost basis, bare metal can be upwards of 90% cheaper than equivalent cloud compute. For many teams with significant cloud infrastructure spend, this cost gap represents a massive potential cost savings opportunity; however, cloud still remains dominant in today’s market. As vendor-agnostic infrastructure tooling has matured, technical blockers to being able to adopt bare metal have lessened, but the economics of elasticity that cloud offers remains the major barrier for many looking to ditch cloud entirely.

At Hathora, we’ve navigated this problem by employing a hybrid approach: using bare metal for cost-effective base capacity, and bursting onto cloud for on-demand elastic compute. This best-of-both-worlds approach is what set us apart for our game server hosting business, and we’re seeing strong pull for this approach in other verticals as well. It’s a shakeup of the established “single cloud vendor” status quo, and we’re excited to be building in this space.